A Clown in the Circus

A personal opinion piece regarding Israel & Palestine by David H. Fuks

Bio: David H. Fuks is an author, an actor, a holocaust educator and a playwright. He is also a serious Jew who worked in the human services arena for over forty years. His parents were Holocaust survivors. Fuks grew up in Detroit, Michigan and has lived in Portland, Oregon for fifty years.

1. – Family

My Hebrew name is the same as my paternal grandfather’s, Chaim Dovid Fuks. He was a Hassidic Rabbi that I would never know. He was one of the six million Jews murdered in the Holocaust. Because I was born in the U.S., my parents gave me an American name: David H. Fuks.

My cousins in Israel are similarly named. Chaya, my Aunt Paula’s daughter, shares my first name. My cousin Chaim Nehemiah, my Aunt Lola’s son, has my grandfather’s first name (Chaim) and my father’s first name in Hebrew (Nehemiah). In the USA, when he became a US citizen, my father became Henry Fox.

During conversations more than ten years ago, Chaya expressed her support of the Labor Zionist Party. Chaim Nehemiah is a retired Lt. Colonel of the Israeli Defense Force (IDF). He is a Likudnik; he leans towards the right. My family in Israel is not unusual. They represent both the politics of fear and the politics of hope.

Chaya once told me that she missed the simpler Israel of the era prior to the 1967 Six Day War. She expresses concern that the conflicts during the occupation of the West Bank and Gaza are sometimes caused by negative behavior from Israeli soldiers who are assigned to manage the checkpoints near Israeli settlements. Palestinians are often questioned and bullied by IDF soldiers in a quest to determine who might have a hostile intention as they travel past Israeli settlements in the occupied territories…or as they journey to work in Israel. “Soldiers are trained to confront people at the checkpoints,” Chaya said. “When they return home, some continue to behave badly.”

During this same period, Chayim Nehemiah once said to me that he felt that something had to be done to limit the development of Israeli settlements in the West Bank. “You surprise me,” I responded. “This is a departure from your perspective as a Likudnik and a soldier.” He smiled at me and explained, “It is much different being the father of a soldier than being the soldier, myself.”

These conversations took place during an era where the politics of hope and the politics of fear were not too far apart. Despite the Intifadas, Israel enjoyed a sense of security while there was also significant debate and, at times, passionate disagreement. There was also a sense of pride in the nation as a homeland and a safe haven for all Jews. It was a time that Israelis were seen as centrists. They took pride in their technical and cultural achievements, remarkable agriculture and sense of safety. When I arrived on visits to Israel, strangers would say, “Welcome home.”

*

2. – History

As a child attending classes in a Yeshiva (an orthodox Jewish parochial school), I was expected to look at the books of Genesis and Exodus…literally. As an adolescent, I was taught to recognize the scripture as a catalyst for argument and complex conversation. As an adult, I am happy to explore the beautiful metaphoric language of our literature and to find the phrases and wisdom that inspire me. I am moved by Isaiah’s admonition that wearing sackcloth and ashes are not enough and that holiness demands that we feed the hungry, clothe the naked and shelter the homeless. I love the phrase in our daily prayers: “In all time, creation is renewed.” It is poetry.

Under Roman rule, we Jews were banished from our homes in ancient Judea in the middle of the second century of the Common Era. We were dispersed across the world with the Roman expectation that we would assimilate into various cultures and disappear. Yes, we did assimilate to some degree. We married whoever was beautiful and kind to us and became the multicultural civilization that we are today. European Jews look like Europeans. Latino Jews look like Latinos. Middle Eastern Jews look like Arabs. Ethiopian Jews are clearly Africans. Yet, our civilization and our religion continues.

But, we have never been able to fully assimilate. After 1,000 years of living in Spain, we were expelled by the Inquisition. After hundreds of years of living in Persia and throughout the Arab World, where the Babylonian Talmud was written, we were expelled. During 1,800 years of living in Europe, we experienced religious antisemitism and then in the 1850s racial antisemitism. Crusaders seeking to recapture Jerusalem would commit atrocities against Jewish villages along the way. Russians restricted us to the poverty-stricken Pale of Settlement and supported pogroms against us.

I had a conversation with my older sister, once, where she was lamenting that her sons were not practicing Jews. “Did you ever light Sabbath Candles with them?” I asked. “Of course not,” she replied. “If you had one word to describe Jewishness, what would that be?” I questioned. “Suffering,” my sister replied. “How about you?” she asked. “Covenant,” I said.

The brilliance of rabbinic Judaism and the remarkable artistic talent of secular Jews informed a culture with a wide range of artistic, philosophical and scientific achievements that has contributed and influenced the world: Nachman of Bratislava, Franz Kafka, Baruch Spinoza, Isaac Babel, Karl Marx, Groucho Marx, Sigmund Freud, Albert Einstein, Bugsy Segal, Jonas Salk, J. Robert Oppenheimer, Larry David, Louis B. Mayer and Philip Roth…you get the picture. In a world of eight billion people, our 13 million has been significant. (Prior to World War II, there were 18 million Jews. We never made up for that loss.)

Zionism was born out of the inability to assimilate in Europe. In the context of the Enlightenment, Jews were offered the opportunity to become citizens. Napoleon convened a Sanhedrin (a group of 70 spiritual Jewish leaders) to ask, “Can you be Jews at home and Frenchmen on the street?” Jews leapt at the opportunity. But early in the 20th century, a somewhat assimilated journalist, Theodor Herzl, came to Paris to report on the Dreyfus trial. Alfred Dreyfus was a Jewish captain in the French military who was convicted of treason based on trumped-up evidence and sent to a prison on Devils Island. Thus, Herzl, in his state of disappointment, realized that it would never be possible for Jews to be fully accepted in Europe. He convened the first Zionist Congress which defined Zionism – the desire for Jews to return to their ancient homeland and to have the sovereignty and self-determination of statehood. Herzl’s dream became a reality after the Holocaust.

*

3. – Some Lessons from the Holocaust

My father, Nehemiah, was the son of a Rabbi, a follower of a Hassidic luminary, the Gere Rebe. He rebelled and, at age 12, became a laborer…eventually joining the union movement.

The hatred of Adolph Hitler and his followers involved a desire to destroy Jewish civilization. They came close to success in Europe. During the Holocaust, my father barely survived five years in the Buchenwald concentration camp near Weimar. My mother was in a slave labor camp near Prague, Oberalstadt, for five years. They didn’t meet until after they were liberated from the camps. They were married in 1945 and lived in a Displaced Persons Camp in Landsberg, Germany for four years.

In 1949, my parents were among the 75,000 Jews in Displaced Persons Camps who were permitted to enter the United States. With the help of the Hebrew International Aid Society and the local Jewish Federation, Detroit, Michigan became our home. My mother’s two surviving siblings also became Americans. My father’s two surviving sisters joined over 300,000 displaced Jews in Israel.

Being a child of Holocaust survivors, I received the dubious gift of vicarious traumatization. This indirect learning had a profound influence on me. The shocking history of my parents was expressed at home and in the community. They were wonderful people who struggled with Post Traumatic Stress and other emotional challenges. My parents’ ethics and love kept us safe. Their personal struggles were filled with life lessons. Their resilience was based on love. But, my father also demanded that I had to refuse to be a victim. I had to learn to fight.

There is a poem in Yiddish that my father shared with me. It described a moment of horror during a pogrom, a violent riot victimizing Jews in Eastern Europe. The poem told of a young man hiding behind a furnace as his wife was being sexually assaulted by Cossacks. “Before the war,” my father said, “Jewish boys were taught to be passive if they were struck by a gentile. It was expected that the thugs would stop eventually. “But now,” Henry demanded, “we must be willing to fight back. Even if we are afraid…even if we are injured…we must show that we are willing to fight.”

My father was a Bundist who spoke elegant Yiddish and led the Detroit chapter of the Workers Circle. As a committed Democrat, my father admired President Truman. Although he lost his faith in God during the Holocaust, he supported my mother’s insistence that I attend a Yeshiva (which I did until I was 14.) My mother also insisted that I have the opportunity to visit our family in Israel. “To succeed in marriage, you must learn to compromise,” my father said.

*

4. – Visiting Israel

I have been to Israel six times. These visits have been remarkable and, upon occasion, challenging.

My first visit occurred after my high school graduation in 1968. I was 17 years old and a foolish American kid. It was a year after the 1967 Six Day War. Israel was filled with pride at its remarkable military achievement. The Labor Party was in charge and the sense of liberal democracy and hope was strong.

I attended a class at a kibbutz in the north of Israel, Gesher Haziv, where a speaker suggested that Israel could broadly expand its footprint in the Middle East. He showed us a map which reflected his hegemonic fantasy. It was hard to take him seriously.

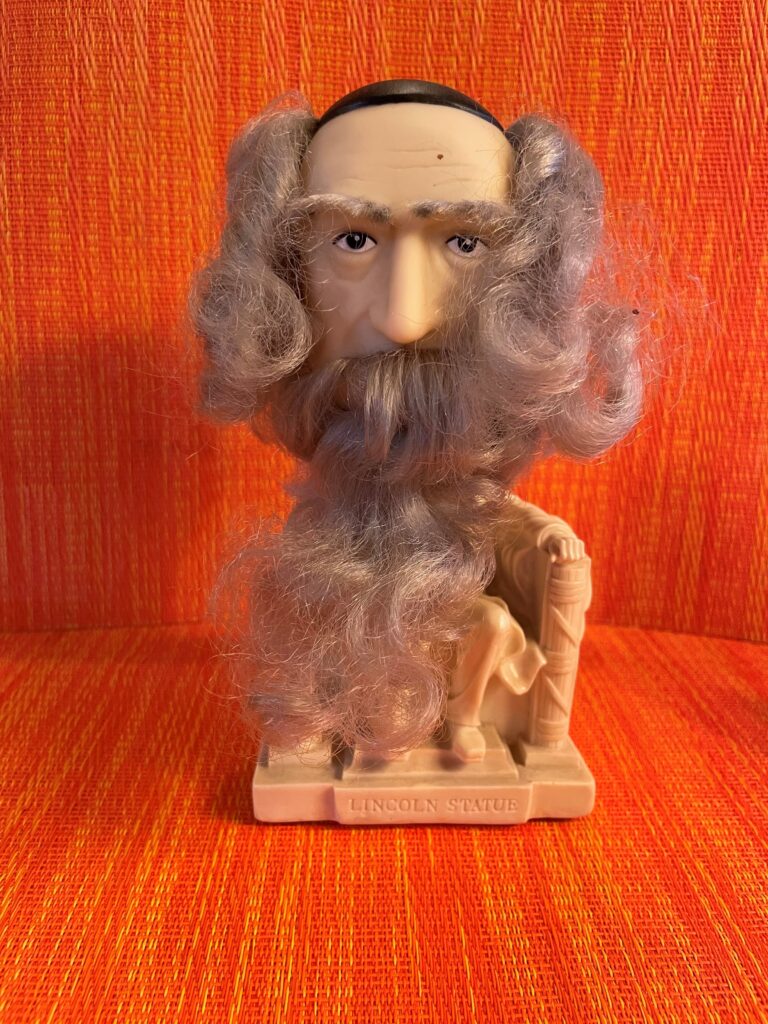

After a week of illness on that trip, I was simply grateful to be feeling well again. In a bakery, in Netanya, as I was joking with my peers, a stranger admonished me. “You should be a clown in the circus,” he said. “I am a clown in the circus,” I replied. The stranger shook his head and walked away.

I didn’t fall in love with Israel. My visit to a kibbutz affirmed my disinterest in both farming and socialism. However, I was amazed to see that the Arab village of Achziv in the north was a ghost town. (Now, it is an Israeli artist colony.) Seeing the newly accessible Western Wall was impressive, but to be honest, I was not moved to become more pious. However, I was touched and challenged by the piety of many Israelis, while observing that others had no interest in religion. In addition to seeing important Jewish sites, this visit was an opportunity to also see ancient churches, to go into the Occupied Territory and to sit in the Church of the Nativity, while priests lead prayers and burned incense. I was impressed to meet my Israeli family and especially to see my father’s face reflected in my aunts and cousins.

Also, I remain surprised at my childishness at that time. My command of Hebrew was limited to words that could get me into trouble, but not out of it: “At kama at? Ma at Oseh b’erev?” (How old are you? What are you doing tonight?) I was a clown in a circus.

*

When I returned to Israel more than thirty years later, I had come to a much more advanced country. Two of those visits were Bar Mitzvah trips for my sons. They enjoyed the touring both in Jerusalem and in the Negev. Our oldest son was intrigued by the shops in the Old City. He enjoyed the city of Tiberius and felt most at home in Tel Aviv. Our youngest enjoyed the city of Netanya and connected with our cousins. At the Kennerit (the Sea of Galilee) our youngest said, “I’m a son of David. Maybe I can walk on water.” Then he exclaimed, “Yikes! My feet are wet!” “I guess we’ll have to wait for the Messiah,” I shared.

My cousin, Chaya, gave us a tour in the holy city of Safed. “This is where Elijah hid from Jezebel,” she said as we drove up a hill. Perhaps it was too much to expect a delicate moment of silence.

After Israel’s Prime Minister, Yitzhak Rabin, was murdered by a radical rightwing settler in 1995, my heart and mind were filled with questions. Later, both of my sons participated in the “Birthright Israel” program and visited the country as college students. Much like many in their generation, they came home with questions related to human rights, as well.

The next three of my visits to Israel were both family visits and missions supported by the Jewish Federation of Greater Portland. There were significant opportunities for scholarship and observation.

On the one hand, I was pleased to see a program supporting disabled individuals through the use of “Community Parents” who carried caseloads of 50 individuals, each. They drove to visit clients regularly and helped with problem solving or provided social support. I was also happy to see schools where Israeli and Palestinian students studied together. Furthermore, the multicultural city of Haifa filled me with hope.

On the other hand, I was shocked to see the walls that had been constructed as a result of a desire for safety after the first and second Intifadas. I was impressed to see, when there was a problem or sense of threat, Israelis moved toward the difficulty, while the tourists held back or retreated,.

Regardless, my discomfort at seeing checkpoints continued to trouble me as did the angry hand gestures of young Palestinians in a passing bus. I found being tapped on the back by a security guard at a café in Jerusalem a bit disconcerting, at first. Then, I recognized this necessity in a place that had been bombed. That tap became, somehow, comforting.

My last trip to Israel was a gift of the Wexner Heritage Foundation. The foundation had made a remarkable investment in educating Jewish leaders across the country. We were exposed to a wide range of literature, and remarkable scholars, educators, spiritual leaders and political leaders from across the globe. This investment shaped the trajectory of my career and my understanding of Jewish history, politics and responsibility. It reshaped my spiritual understanding of Jewish literature and holidays and led me further into Jewish community service.

This trip to Israel for the purpose of study was both a delight and a challenge. The plenary sessions exposed us to political leaders on the Right and the Left. Again, the discussion was focused on the politics of hope and the politics of fear. It was clear that fear was emerging as the dominant emotion in Israeli politics. (I had cousins who had high regard for Prime Minister Bibi Netanyahu…and other relatives who had contempt for him.)

We heard from an ultra-orthodox Haredi leader who I found too rigid and too certain in his faith. There was no willingness to question the theocratic status quo. For example, the domination of this religious population restricted the ability of all Jewish Israeli women to get a fair divorce. Unless the husband signed a Get – an Orthodox document in agreement to the divorce – a civil agreement could not take place. Desperate women were often intimidated…and financial settlements left them impoverished.

We also heard from a West Bank Jewish settler who was speaking for his movement. A question was raised to this USA-born leader regarding the issue of “land for peace” – a hoped-for element of pursuing a two-state solution. He was asked to consider a choice between the land in the West Bank and democracy. In his clear North American accent, he replied, “I choose the land.”

My despair was abated by a visit with a friend and colleague, a Clinical Psychologist. He took me to the home of a Palestinian-Israeli mayor of a small village near Jerusalem. The spiritual time of Ramadan was under way and we attended a dinner after a day of fasting. There, I met a social worker from Ramallah, a principal city in the West Bank. These two professionals were providing mental health and social services to Arab children. The piety, generosity and mutual commitment to be of service was heartening.

Much like my sons, my visits led me to more questions than answers.

*

5. – Our Arab Daughter

Several years ago, during the winter holiday season, my wife and I were approached by a friend asking us to help an Iraqi student who was currently experiencing a year abroad at the University of Oregon. Leila (not her real name) was a young Arab woman from Baghdad, who had left the country of her birth and enrolled in a four-year university program in Japan. The year she spent in the United States was a part of her educational program. We agreed to have her as a guest for the winter break.

Leila, a beautiful and smart young woman, had decided in Japan to set aside her head scarf and was becoming acclimated to the opportunities she was being given in both Japan and the US. She had mastered both Japanese and English and was developing an interest in international trade. She had no experience in a Jewish home and our experience in the Arab world was limited to our travels to Israel. Yet, she quickly opened her heart to us and we reciprocated.

We were happy to share our family home with Leila. She was accepted into our young son’s circle of friends and accompanied my wife to a holiday choir practice. We also visited the tourist sites of Portland and surrounding areas. Leila enjoyed the hospitality and commented that she appreciated the firsthand learning about a Jewish family. We enjoyed celebrating Hanukkah with her and delighted in getting to know her Baghdad family via FaceTime.

I took Leila on a tour where I worked as CEO of Cedar Sinai Park – a Jewish agency that provides healthcare and housing to seniors and people with disabilities. At the end of her stay with us, Leila asked if it might be possible to have a summer internship at Cedar Sinai. I said, “Ours is a non-profit healthcare organization, we’re not exactly involved in international business.” “As a young Arab woman in Iraq, I have had no real work experience,” she explained. “I need a chance to learn.”

I agreed to Leila’s request. With my wife’s support, we invited her to live with our family for the summer. Thus, a young Iraqi woman who was a Shia Muslim and whose father, of blessed memory, was Kurdish, became a member of our family and a volunteer intern in a Jewish organization.

Leila’s assignments over the summer included meetings with various department heads, participation in management team meetings, and the development of a PowerPoint slide show focused on comparing the Jewish values of care for elders with the Moslem values of such care. She presented this slide show to our staff. We were happy to see the remarkable similarities regarding this faith-informed responsibility.

During that summer, a courtship (overseen by my wife and me acting as protective substitute parents) began for Leila with a young Sunni Muslim Iraqi man named Rashid (not his real name). He was an engineering student and was living in the home of a former Captain in the Army Corps of Engineers. Rashid had been a translator for General Petraeus and came to the US when that responsibility came to an end.

Rashid’s and Leila’s romance was fruitful, and after she finished her scholarly work, they decided to get married. While Rashid’s mother and sisters were in the United States, Leila’s mother and brother were unable to leave Iraq. So, Leila asked me if I would walk her down the aisle during her wedding. Thus, a Jewish man walked a young Shia Muslim woman down the aisle to marry a Sunni Muslim man in a wedding ceremony officiated by a Protestant Christian minister. It was a very American celebration!

Leila and Rashid (who now goes by the name “Robert”) live in Minnesota. Robert is now a US citizen and Leila will soon follow suit. They have two beautiful children. Affection and exposure has made our relationship to this family a gift I was honored to receive.

*

6. – Reactions to the Gaza War

Desperate people do desperate things.

When I was a teenager in Detroit, a riot broke out and the city was under a curfew. A strategic group of very big, white and violent police officers known as the “Tactical Mobile Unit” was among the factors that triggered this crisis. The outcome in the Black community at first seemed self-destructive and fruitless. Black neighborhoods were burning. Stores were being looted. Tanks were patrolling on Eight Mile Road. It took many years, political changes and community leadership to see my hometown heal.

The October 7, 2023 Hamas invasion of Israeli kibbutzim and a music celebration was the worst attack on Jews since the Holocaust. The brutal taking of 250 hostages, the use of sexual assault as a weapon of war, and the murder of 1,200 Jewish citizens of Israel was traumatic.

The apparent failure of the IDF and the Mossad, the Israeli intelligence agency, to anticipate this horrible event cast a negative light on the Netanyahu-led leadership of the country.

Furthermore, Israel’s strategy over the years of allowing millions of dollars to flow from the United Arab Emirates to Hamas leaders had backfired. This “divide and manipulate” policy allowed Hamas to grow in strength, while weakening the West Bank Palestinian Authority. With President Biden’s and Congress’ support of Israel, Israel’s war on Gaza has been underway for eight months. Hamas has been severely disabled and deserves to be destroyed. However, it must be recognized that the strategic outcomes Prime Minister Netanyahu has touted – to destroy Hamas – seems far off. Gaza is in rubble. This level of destruction and the number of dead – nearly 38,000 Palestinians, many of them innocent children – is unconscionable.

I am stunned. I am shocked. I am heartbroken.

Yes, a military reaction was necessary. Yes, Hamas hides behind a human shield of Palestinians. Yes, the Israeli hostages must be released. Regardless, this is an unbearable circumstance.

The context must also be observed. The past failures to work out peace agreements in the Oslo Accords (1993-1996) and effort at Camp David in 2000 were significant failures. The havoc of the two Intifadas has resulted in a politics of fear and a more oppressive experience for Palestinians and a more aggressive relationship with the IDF. Furthermore, the level of civilian collateral deaths may likely motivate the next generation of terror. A tactical victory is not a strategic victory.

When Israeli West Bank settlers destroy Palestinian homes and communities with impunity, while Israeli soldiers and police look the other way, it damages the fabric of Israel and increases the desperation and anger of the Palestinians.

When children and their parents are suffering from famine, and when water, food supplies and healthcare are unavailable, it brings the Jewish values of ethical monotheism into question.

When parents and their friends in Tel Aviv are ignored when pleading to move forward with a ceasefire in order to bring surviving hostages home…and an effort to rekindle the hope for peace gains no traction…the leadership of Israel’s current government must be questioned.

Here in the United States, we are seeing a significant increase in antisemitism. Jewish students are being victimized and universities seem unable to keep campus life safe. This is not acceptable.

Meanwhile, some politicians bluster and seek partisan advantage. This is not leadership.

As a serious Jew and an active member of my Jewish and American communities, I have often shied away from Israel advocacy. “I’m a local policy guy,” I have said. “Israel is an important issue, but it is not the only Issue,” I have said. “Let’s talk about Medicaid and Social Security,” I have said.

I have been timid in the face of possible scorn from my own community. But as a Jew, I have been taught that all humans are made in God’s image. I have been taught that we must be kind to the stranger because we have been strangers, as well. I have been taught that holiness requires that we feed the hungry, clothe the naked and shelter the homeless.

Yes, we must protect our children from antisemitism. Yes, we must defeat Hamas. But we must also examine the strategic and policy failures of the response to this crisis by the current ultra-right wing leadership of Israel.

As an adult descendent of Holocaust survivors, I have been proud of the Jewish state. It is important to the future of our 4,000-year-old civilization. It is expected to be a haven for Jews in a dangerous world. But, I grieve at the impact of the Gaza war violence and the greedy administration of West Bank settlers.

The time has come for an honest reckoning. We must support a moral IDF and speak with concern for the soldiers involved in this war. We must rekindle the politics of hope and seek to build a peace where both Israel and Palestine have sovereign rights. We must demand that Israel conduct itself as a state committed to ethical monotheism rather than retribution.

We have serious work to do. It won’t wait for Yom Kippur.